Unleashing Productivity in 12 Steps: A Practical Guide

Wishing you all a productive 2024!

Hi Lab,

Happy New Year - I hope you all had a restful break! Classes begin next week and so I’ve been tying up loose ends on projects and deciding what I want to focus on this year. I thought I’d write my first substack of the year on my personal approach to productivity - apologies for the Buzzfeed headline!

Those who know my research and broader work, know that I do a lot of different things:

I research and write papers (and recently a book) on a wide array of topics that relate to genetic and cultural evolution, from corruption to whales and dolphins to religion to culture and behavioral science to genetics to historical psychology, cooperation, measuring culture, measuring parsimony in statistical models and the occasional collaboration on Frontal Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats or spontaneous dynamic hierarchical organization in a non-uniform life-like cellular automata.

I develop software, including the Database of Religious History and Culturalytik

I speak, consult, and run training for governments and companies

I teach undergrads, summer schools, Masters, and direct a PhD program

I do science communication from documentaries to radio shows and various interviews

I raise 3 children

I try to be a good husband, colleague, friend, and human being

It’s a lot, so I have to be careful in how I invest my time. Investment is exactly how I think about productivity - I think about the expected value return on how I spend each year, each month, each day, and each half hour.

In A Theory of Everyone, I wrote:

We all face a trade-off in how much time to allocate to work, to our families, to our friends, and to ourselves. In tackling this trade-off, I personally am obsessed with efficiency. I’ve spent years figuring out how to maximize my use of the twenty-four hours I have each day, the fifty-two weeks I have each year, and the eighty or so years the average Western male gets for a lifetime. This obsession includes how to efficiently distribute my cognition in a way that prevents my to-do lists and project prioritization tools from getting in the way of focused deep work; how to hack my psychological limitations by doing things like leaving work unfinished at the end of a day to make it easier to restart the next (an application of the Zeigarnik effect); accepting that while it is inevitable that I will procrastinate, it is not inevitable what I will procrastinate on – I can procrastinate by working on low priority things that do actually need to get done – productive procrastination; and even how much time to spend on optimization itself and how much free time I need to ensure there’s space for spontaneity.

My obsession even extends to how to efficiently be a better parent to my three children, efficiently be a better partner to my spouse, and how to efficiently relax.

To quickly relax my mind, I find sensory deprivation tanks a cheat code to meditation. I float with ear plugs in a pitch-black tank filled with body temperature Epsom-salted water, like a personal perfectly warm Dead Sea. After a few minutes, my mind wanders and then starts to self-organize. My anxiety and stress dissolve in the water.

To quickly relax my body, I stress it. Apart from lifting weights, one of my favorite ways to stress my body is by profusely sweating in a German Aufguss sauna ceremony. For ten to twelve long minutes, gloriously scented, steamy air heated to at least 85°C (185°F) is whirled and beaten around the room and at participants by a skilled Aufguss sauna master. Blood rushes to your brain and body. Stress-free participants stagger out of this communal ritual to a short warm shower followed by an icy cold 4 to 5°C (40°F) dip.

But here’s the rub. No matter what weird psychology or ceremonies I use, there is a limit to my efficiency. At the end of the day, I still have only twenty-four hours, of which continued efficiency requires eight dedicated to sleep – efficient sleep of course, optimized for letting ideas ruminate. Imagine how much more you or I could do if we had more than twenty-four hours.

There are ways to get more than twenty-four hours.

The book goes on to discuss the role of energy, technologies, and cooperating with others. Here I want to take a step back and show you how I think about productivity overall.

Back to the Buzzfeed headline.

Unleashing Productivity in 12 Steps: A Practical Guide

1. Understand Your Ultimate Why

Productivity isn’t just about doing more; it’s about doing what matters. So you need to start by asking yourself: “What am I trying to achieve?” This could be career-oriented, personal development, or even leisure goals. Knowing your ‘why’ helps prioritize tasks and keeps you motivated.

My dog, Suzie, died when I was 8. Since then, I’ve been captivated by the inevitability of death, or at least my own mortality. My grandfather died when I was 16 and one of my best friends, who I’d known since Grade 6 died when I was 17. We were in our last year of high school. These were stark reminders that our time is finite. We’re all going to face that final curtain one day, so I find motivation in asking: “What do I want to achieve before that moment?”

Steve Jobs was similarly motivated:

Source: https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/427317-remembering-that-i-ll-be-dead-soon-is-the-most-important

It’s about running the tape backwards from the end - envisioning what you’d like to have accomplished when you’re looking back on your life. This perspective isn't morbid; it’s a powerful motivator that’s always in the back of my mind. It should urge us to make meaningful choices and to spend our time on earth in ways that resonate with our deepest values and aspirations. In this light, productivity transcends efficiency; it’s a race against time to imprint our existence with purpose. For me that purpose is to try to leave the world a better place than I found it.

Biologists talk about ultimate vs proximate explanations:

Ultimate explanations delve into behavior or traits in terms of evolutionary advantage. We like sweetness more than bitterness because fruits and vegetables at their peak of calories and vitamins have more fructose and animals that can detect and prefer this moment do better than those that don’t. Bitterness is associated with poisons.

Proximate explanations, on the other hand, focus on the mechanisms and processes. When we eat sweet foods, the mesolimbic system - the brain’s reward system - is triggered. But that’s because evolution has made it sensitive to sugars - it could have been triggered by bitterness if that had a better evolutionary advantage. The ultimate and proximate go hand in hand.

My Ultimate Why is that I see problems in the world and on the horizon that I want to figure out how to fix.

How do we live on a climate changed world?

How do we design immigration policies that are good for existing citizens and newcomers?

How do we ensure cooperation and strong institutions under mass migration?

How do we create a better match between opportunity and talent, nurture the abilities of more people, and spark a creative explosion?

I can’t address these problems alone and certainly not implement them, but I can spend my time focusing on the things I think others are missing and think about how they might be implemented. It’s the subject of Part 2 of A Theory of Everyone. In an introduction to my HBES plenary a couple of years ago, Joe Henrich described this approach as “mission driven”:

Your Proximate Why works best when connected to your Ultimate Why. You need to think about your reward systems and make sure they’re connected to your goals. One heuristic is to think about the moments when you were in a state of Flow. You were immersed in whatever you were doing to the exclusion of all else. You felt happy. You felt like you in the right place. Ask yourself, “Who was I in those moments?”.

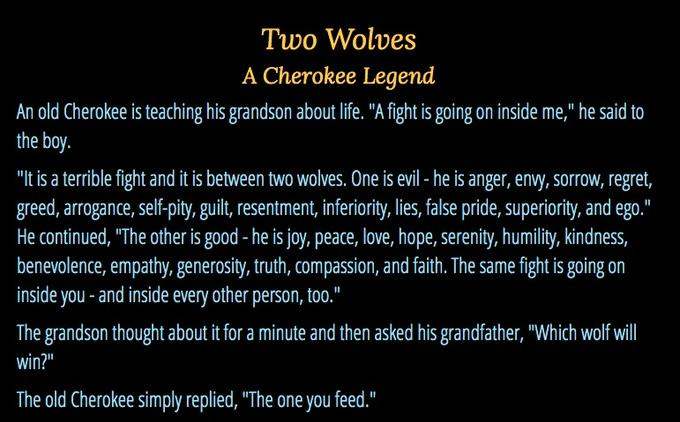

There’s a meme about how inside you there are two wolves - one good and one bad. The wolf that wins is the one you feed.

Source: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/inside-you-there-are-two-wolves

Maybe. But, there are also different people. There are different Yous that also need to be fed.

For me, there’s at least 5 Me’s:

The Parent who finds pleasure in teaching and learning from his kids and has joy and flow in many of those moments (but also frustration and boredom - the days are long but the years are short!).

The Public Speaker who is energized by spreading knowledge from a stage to as many people as possible in an engaging way as possible.

The Scientist who hits flow in careful analysis to uncover truths that others have yet to see.

The Mentor who finds satisfaction in helping other people achieve their potential and become their best selves.

The Engineer who takes pride in building things that last.

There are more Me’s - The Husband, The Friend, The Entrepreneur, The Volunteer, and so on. To be a happy and contented person, you must get to know and feed the different You’s and which ones generate the most Flow and satisfaction. An ideal life in one structured to maximize these moments.

2. Follow Your Biorhythms

My wife, Steph, is not a morning person. I’m not a morning person either, but she’s barely a person in the morning and becomes human around 12pm and a productive person around 5pm as I start to fade into uselessness. I’m alert by 7am and peak between 11am and 2pm. It works well for us that we’re different.

Each of us is different. You’ll see advice about getting up at 5am or how mornings set the tone for the day. I’m with those who think we give too much power to morning people with their 9am meetings. But there are more birds than just larks and night owls.

One important aspect of productivity is getting to know your own unique biorhythms - when you’re typically energized and you’re typically flagging. Adjust what you do during those times.

Schedule the focused, deep, important, difficult work when you’re at your best. Reply emails, deal with bureaucracy and administration, cook and clean, process your receipts and take your boring meetings when you’re not.

3. Prioritize Ruthlessly - Scientists vs Engineers

My advisor, Joe Henrich, and I share a background in engineering. It was only after I met Joe that I noticed a fundamental difference in how scientists and engineers are trained to think. Scientists often delve deeply into a specific segment of the world, aiming to understand it in its minutest details. This approach is essential for deep, nuanced understanding. Good engineers think differently; they can’t afford the luxury of such narrow focus. Instead, they must maintain an understanding of how their specific part integrates into a larger system. This trains an ability to zoom in and out of a problem, grasping both the minutiae and the overarching system.

Applying this principle to productivity, not all tasks are created equal. Some tasks are embedded in the details, while others are instrumental in setting the broader context. The better you get at zooming in and out to see the map and each specific turn, the more effective you’ll be in getting to where you want to go.

Tasks also vary in their importance, urgency, and amount of work required. To prioritize my tasks, I use a variation of the Eisenhower Matrix that also includes amount of work:

Source: https://asana.com/resources/eisenhower-matrix

Each project is assessed for its anticipated impact (high, medium, low) and required effort (high, medium, low). I then sort tasks by highest impact and least effort. In addition, I try to focus on projects and tasks that align most closely with my goals, and set aside or delegate less aligned or less critical tasks. My full set up and list of tools and apps is in a follow up email for paid subscribers.

4. Become a List Processing Machine

David Allen, in his productivity philosophy, refers to the concept of having a ‘mind like water’, drawing inspiration from Bruce Lee’s famous metaphor. David defines this as, “A mental and emotional state in which your head is clear, able to create and respond freely, unencumbered with distractions and split focus”.

The key to achieving this state is externalization.

Externalization means taking what’s in your mind – your tasks, ideas, plans, and worries – and putting them somewhere outside of yourself. This could be in a journal, a digital tool, or any system that works for you.

By externalizing, you free up mental space. Instead of trying to remember everything or getting overwhelmed by a mental to-do list, you allow your mind to focus fully on the present task. This not only improves concentration but also reduces stress and mental clutter.

In practice, externalization might involve daily, weekly, monthly and yearly planning sessions where you lay out your tasks and objectives. I’ve just finished externalizing my yearly focus for 2024.

It also means having a system for capturing ideas and thoughts as they come, so they’re not lost, but also not distracting you. It could even be storing the idea in other people’s heads or knowing who to turn to if you want to know something.

I’m not rigid about the Getting Things Done philosophy or the system; it’s more about having a reliable place to store information and know where a task is at, how important, urgent, and amount of work it needs, how it connects to the bigger picture, who’s responsible, and what needs to happen next, so your mind isn’t trying to juggle it all. It’s about creating a workflow that allows you to engage with your tasks one at a time, fully and without distraction, much like water that flows over and around obstacles.

5. Collaborate, Cooperate, and Focus on Your Comparative Advantage

Mathematician and physicist, Stanisław Ulam (who was unfortunately left out of the recent Oppenheimer movie!) once asked economist Paul Samuelson (who won the second ever Nobel Prize in economics) to name one idea in economics that was both universally true and not obvious. Samuelson went away and came back with the principle of comparative advantage.

Comparative advantage means focusing on what you can do better or more easily than others. It’s about playing to your strengths and acknowledging that you can’t be the best at everything. When you apply this idea to your work, it encourages you to invest time in areas where you excel, while being open to collaboration and cooperation in other areas. This is where the true power of teamwork and technology, like AI, comes into play. Collaborating with others allows you to complement each other’s skills, creating a synergy where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s about finding those win-win situations where everyone’s unique strengths are utilized effectively. These days, AI tools can be used to handle repetitive tasks or increase your abilities in your weaknesses or make you more creative in your strengths.

Long story short, don’t try to do everything yourself and find ways to bring others on board for mutual benefit. Remember also that there’s no limit to the amount of good you can do it you’re willing to let others take the credit.

6. Embrace the Power of 'No'

Time is finite. Every ‘yes’ to something trivial is a ‘no’ to something vital. Learn to tell the difference and decline requests that don’t align with your priorities - your Ultimate and Proximate Whys. Here’s where an investment mindset is helpful.

Beyond task management, I take an investor-like approach to risk management. My focus is usually divided among three types of projects:

‘boring but important’ ones that ensure stability and progress of my goals

‘exciting and probable’ ones that keep me engaged and have likely success, and

‘moonshot’ projects that, while risky, could potentially lead to groundbreaking discoveries and achievements.

This diversified portfolio approach in project selection not only balances risk but also keeps the work dynamic and fulfilling.

Saying no also means saying no to existing projects where the expected return has changed with new information. Triage ruthlessly and don’t fall for the sunk cost bias - persisting with a project simply because you’ve already invested a lot of time and energy. Dump projects that are going nowhere or not going where you expected and pick another item from your list.

As a psychological hack, I put these projects into an “on hold” pile to be revisited later. Of course, I never do.

7. Hack Your Psychology: Productive Procrastination, Pomodoro Technique, Ziegarnick and other Hacks

My friend, Dave Liu graduated as one of the top engineers in his cohort, went on to do a PhD in biomedical engineering, got bored, went back to med school, became a consultant anesthesiologist, and now works as a critical-care clinician-scientist-engineer. One of the secrets he imparted on me was productive procrastination.

It’s hard not to procrastinate, but you can choose what to procrastinate on. Have a list of things that are boring but need to done - emails, receipts, merging duplicates in Zotero, or organizing your to do list - and procrastinate on those to keep moving forward.

Productive procrastination is an example of hacking your own psychology to protect you from your own foibles. I could write another book on other hacks, which range from:

doing boring work in focused Pomodoro bursts (25 minute sprints with a 5 minute break)

Leaving work unfinished at the end of a session or day to make it easier to start the next day

Do something small to get started. I like Rob Henderson’s example

8. Minimize Distractions

My meetings used to be everywhere - spread throughout my day and throughout my week. I was working in the gaps between meetings. I was quick to respond to emails. Often, I was replying those emails in those gaps! In other words, I was letting other people create my calendar. It’s easier to take control of your schedule as you become more senior, but throughout your career, you must schedule time for deep work.

Chunk your meetings during specific times, with rare exceptions. Turn off non-essential notifications. Reply emails and messages in bursts (productive procrastination!). Schedule time for deep work where you focus on those important, difficult tasks that move you closer to your goals. It’s very easy to be busy but not get anything done.

Sometimes, the biggest productivity boost is simply not being interrupted.

9. Keep Learning and Don’t Forget

Keep a commonplace book, such as a Zettlekasten to capture your knowledge. Externalize the connections between the things you know. Writing an expansive book like A Theory of Everyone would have been nearly impossible without a system that could capture the details of what I’ve learned. My specific setup is in another email.

The general point is to have a way to give you access to a mix of what everyone is talking about and what only a few people are talking about. For the former, there’s the news and social media. For the latter, there’s reading outside your discipline, being part of forums and communities of people not in your social circle, learning from those you vehemently disagree with, small conferences and workshops, and scouring the less visited parts of the Internet or Wikipedia and diving deeper through textbooks and specialist handbooks.

Stay curious and keep learning with the caveat that you should watch your input to output ratio and making sure you’re not just a collector of knowledge, but a person who exploits that knowledge, producing insights and content, putting that knowledge to good use.

10. Wellness Matters: Have A Reset Device

Japanese have onsens, Koreans have jjimjilbang, Germans and Scandinavians have saunas, aufguss and löyly ceremonies.

In the Anglo world, we typically socialize with alcohol. Whatever it is, it’s useful to have your Reset Device. Your Reset Device is what brings you back to baseline, energized to keep going. Depending on your budget, interests, and where you live, it could be walks through the forest, a swim in the ocean, time with friends, a hot tub, massage, or sauna.

I’ve hit the email limit! Continued here:

![The Eisenhower Matrix: How to Prioritize Your To-Do List [2023] • Asana The Eisenhower Matrix: How to Prioritize Your To-Do List [2023] • Asana](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!QH0-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8596cb5f-3f99-45a2-9d20-b61f2ce44eb5_1801x1847.jpeg)