Part 2: My background and why I wrote

LSE Launch event online and in person Sept 28

Hi Lab,

This is a long post telling you a little bit about my background and why I wrote A Theory of Everyone. You can find Part 1 here:

Part 2 continued

I couldn’t shake the sound of Khan’s thick Yorkshire accent as he explained in perfect English, ‘Until we feel secure, you will be our targets.’ The ‘you’ he refers to in his grainy video are his fellow Brits; the ‘we’ are a people who live thousands of miles away in countries that he had only briefly visited yet to whom he feels a greater connection.

These were second generation migrants, roughly my age and who looked a lot like me. Yet somehow Khan and others like him felt like outsiders in their own country. What had gone wrong? What could be done better?

These were formative memories set against my otherwise unremarkable, if peripatetic life, living in these countries and also Australia, Canada, America, and most recently Britain. When you live in so many places, you see how we differ and how we are connected.

We swim in different shoals but we are fish in the same body of water. For the last two decades I’ve been obsessed with understanding these differences and these connections.

Why was Botswana less corrupt and on many metrics more successful than South Africa?

Why was Papua New Guinea so much poorer and less peaceful than Australia?

What are the differences between the multicultural and immigration policies of Australia, Canada, the United States, and the countries of Europe?

When I graduated from high school, I was on a quest to figure this all out. I enrolled in an engineering degree, which seemed like a secure, well-paid career. Unlike law and medicine, it also had international accreditation, a great fit for someone with itchy feet.

Engineering was fun and I was good at it – but engineering alone didn’t seem like it could answer the questions that possessed me, so I enrolled in a dual degree. In parallel with courses on calculus, discrete math, and machine learning, I took courses in economics, political science, biology, philosophy, and psychology. In each discipline I found solutions to a piece of the puzzle.

I ended up majoring in psychology in my second degree. Psychology was asking the most relevant questions about human behavior. But it seemed to flout what I was learning about the scientific method in engineering and philosophy of science. There was little attempt to falsify predictions and the idea of selecting between theories – model selection – was difficult without a theory of human behavior. Evolutionary biology was a good candidate to develop that theory of human behavior.

When evolutionary biological theories were applied to humans, they could make good predictions about human behavior, but evolutionary theories developed in psychology independent of biology relied on too many imprecise assumptions about ancestral conditions and for some reason didn’t use the powerful biological mathematical toolkit. Could we build better models of human behavior?

I eventually gave up trying to answer these questions – it just seemed too difficult. I focused instead on a dissertation about smart home technologies. But the questions kept bugging me, bubbling away at the back of my mind.

Around 2007 I saw Al Gore’s climate documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. Gore argued that we urgently needed to reduce carbon emissions.

As our planet heated, so too would politics, and as places became too dry, too hot, or under water, millions of people would need to flee as their homes and livelihoods disappeared. The more I read, the more convinced I became that Gore was right about the problem but too optimistic about the solution. Would we really slow the economy to save the planet? This wasn’t like the successful ban on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) from deodorants and refrigerators that was helping to close the hole in the ozone layer. In that case, alternatives were available – the market had a solution.

But for climate change, Gore was asking us to cut back our production, wealth, and lifestyles in a world where every country was trying to outcompete every other country, every company was trying to outcompete every other company, and every person wanted a better lifestyle than their neighbors’. It seemed to me that in the absence of a global government and credible enforcement, no amount of documentaries or finger wagging would work.

It made sense that we should still try to reduce our carbon footprint, but it made even more sense to also start preparing for a climate-changed world. And neither Greenpeace nor Captain Planet were asking us to pay attention to the latter. In the meantime, reports from the Pentagon and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) were predicting climate fluctuations and the mass movement of displaced people from places like the Middle East, Bangladesh, and the South Pacific.

I could see research on climate engineering to deal with carbon capture and wild weather, but not enough adaptation research on how to deal with mass-scale refugee resettlement or ensuing conflicts over scarce resources. We desperately needed a science of culture. One mature enough to be trusted and that could be used to develop social technologies. It was in engineering that I finally saw a breakthrough that might help us get there. And it came from the design of smart homes.

Smart homes require what are called control systems. These systems control functions such as temperature & lighting. A thermostat is a simple control system that measures the temperature and turns on heaters or air conditioners to keep a house at the right temperature.

Control systems rely on a body of math called control theory – the math of feedback loops. My insight was that perhaps control theory could be applied to model the feedback loops of people trying to influence one another to develop a science of norms. And from a science of norms we might begin to develop a science of culture and institutions. I needed to find someone who studied the psychological foundations of culture. What do you do when you want to find someone who studies the psychological foundations of culture? You google the psychological foundations of culture.

This led me to a book with that very title edited by an evolutionary psychologist called Mark Schaller, from the University of British Columbia. I emailed Mark describing my background and goals and asking if we could meet. Mark suggested I also meet his colleagues, cultural psychologist Steve Heine, social psychologist of religion Ara Norenzayan, and in particular, former aerospace engineer turned anthropologist then appointed in economics and psychology, Joe Henrich.

Joe was working in an area called dual inheritance theory and cultural evolution, mathematical frameworks for modelling the co-evolution of human genetics and culture (our dual inheritance) and the evolution of culture and institutions. He was applying these models to psychology and economics. After a short conversation I knew that between Joe, Mark, Steve, Ara, and their colleagues, I would have an ideal team to help me tackle the questions I so desperately wanted to answer.

After completing my dissertation at the University of British Columbia a year early, having cross-trained in evolutionary biology, statistics and data science, economics, and psychology, I moved to Harvard’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology and then to the London School of Economics, where I am currently professor of economic psychology and affiliate in developmental economics and data science.

Working across multiple disciplines has allowed me to take a non-disciplinary – or perhaps ‘undisciplined’ – approach, pulling on strands deep within psychology, economics, biology, anthropology, and elsewhere, tying them together into a tapestry that reveals who we are, how we got here, and where we’re going.

Once you see the links between energy, innovation, cooperation, and evolution, you can’t unsee them. These are underlying laws of life that apply to bacteria and businesses, cells and societies. Remember the parable of the blind men who encounter an elephant and try to describe it? One feels its trunk, others its tusks, body, or tail. From their individual vantage points each describes the elephant as a snake, spear, wall, or rope.

By necessity, different disciplines focus on different parts of the system, but when you put the pieces together you can’t ignore the elephant in the room: energy, the innovations that lead to more efficient use of energy, our capacity to cooperate for mutual benefit in the quest for greater energy, and the forces of evolution that shape all three.

But this book is not about coal, it’s not about oil, it’s not even about renewables or nuclear. It is about the future of humanity; about how each of our actions contributes to a collective brain. It’s about how Homo sapiens can reach the next level of abundance that leads to a better life for everyone and perhaps one day a civilization the spans the galaxy. And it’s about the things that stand in the way of getting where we need to be and what we can do to overcome them. Because today we stand on the shore of a sea of possibilities. We must be careful in how we address the coming waves ahead of us; waves that threaten our now precarious fossil-fueled civilizations.

In Part 1, we’ll discuss how one goes about building a science of us; how energy, innovation, cooperation, and evolution have shaped all of life and all human activity; how we learn from one another, what shapes our intelligence, how we can become more creative and increase our capacity for innovation, how we work together and build institutions, and how the laws of life have shaped every aspect of us and our societies. That is, we will see how an unremarkable African ape ended up able to make Zoom calls across the planet.

In Part II we will zoom out to explain why the world is changing, what we can do about it, and why the twenty-first century may be the most important in human history. It is imperative that we reach a new level of energy abundance. But there are barriers standing in our way.

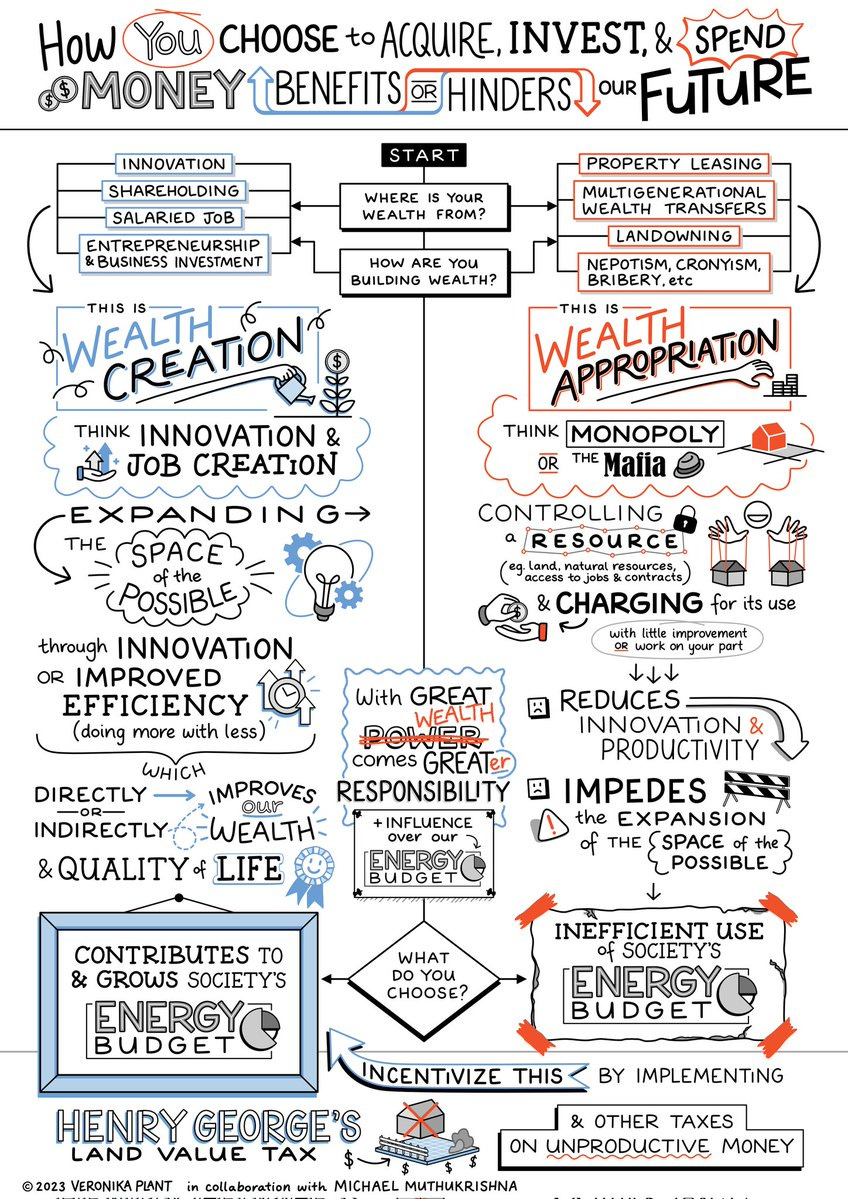

Polarization and corruption threaten to tear us apart. Inequality can (though not necessarily) lead to inefficient allocation of our energy budget. These in turn lead to an inefficient allocation of talent and opportunity, stifling the next creative explosion that we so desperately need. There are many diagnoses for the problems we face, but fewer solutions. Yet solutions do exist. These solutions include how we can design better immigration policies or target taxes on unproductive money.

Other solutions are more radical but worth pursuing, such as start-up cities and programmable politics. In essence, we will discover how this comprehensive theory of everyone can lead to practical policy applications – things you and I can advocate for to ensure that our children and all Homo sapiens who follow – have a future.

So that’s the backstory. I’d like invite you all to join me for the book launch at LSE next Thursday Sept 28th, in person or online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/Events/2023/09/202309281830/theory

As I said, it will be a fire side chat with The Time’s journalist and former Olympian Matthew Syed. There will be plenty of time for questions, discussion, and book signing if you’re there in person.

For more content on my research A Theory of Everyone, please subscribe. Remember, paid subscribers go into a draw to win one of 10 signed copies. All founding members will receive a signed copy and an opportunity to chat about the book.

They can be shipped anywhere in the world.

Best wishes,

Michael