More money, more problems

What is money and where does it come from?

Hi Lab,

Elon Musk’s tweet about money inspired me to dust off some writing I had previously cut from my book, A Theory of Everyone. In an early draft, I had gone into extensive detail about what money fundamentally is and how it functions in society. However, early readers felt this section distracted from the core thesis of the book.

I thought Musk’s provocative tweet provided a great excuse to resurrect and share some writing on:

What exactly is the money supply?

What does it mean to print money?

How is new money created?

And what does it mean to have money that isn’t spent such as through wealth passed beyond a lifetime, a Swiss bank account, or a 401k pension?

What is GDP and what is inflation?

Readers of my book will recognize how this fits into the discussions on economic growth and taxes, in particular land value taxes. Let me know what you think in the comments below or on social media.

What is money?

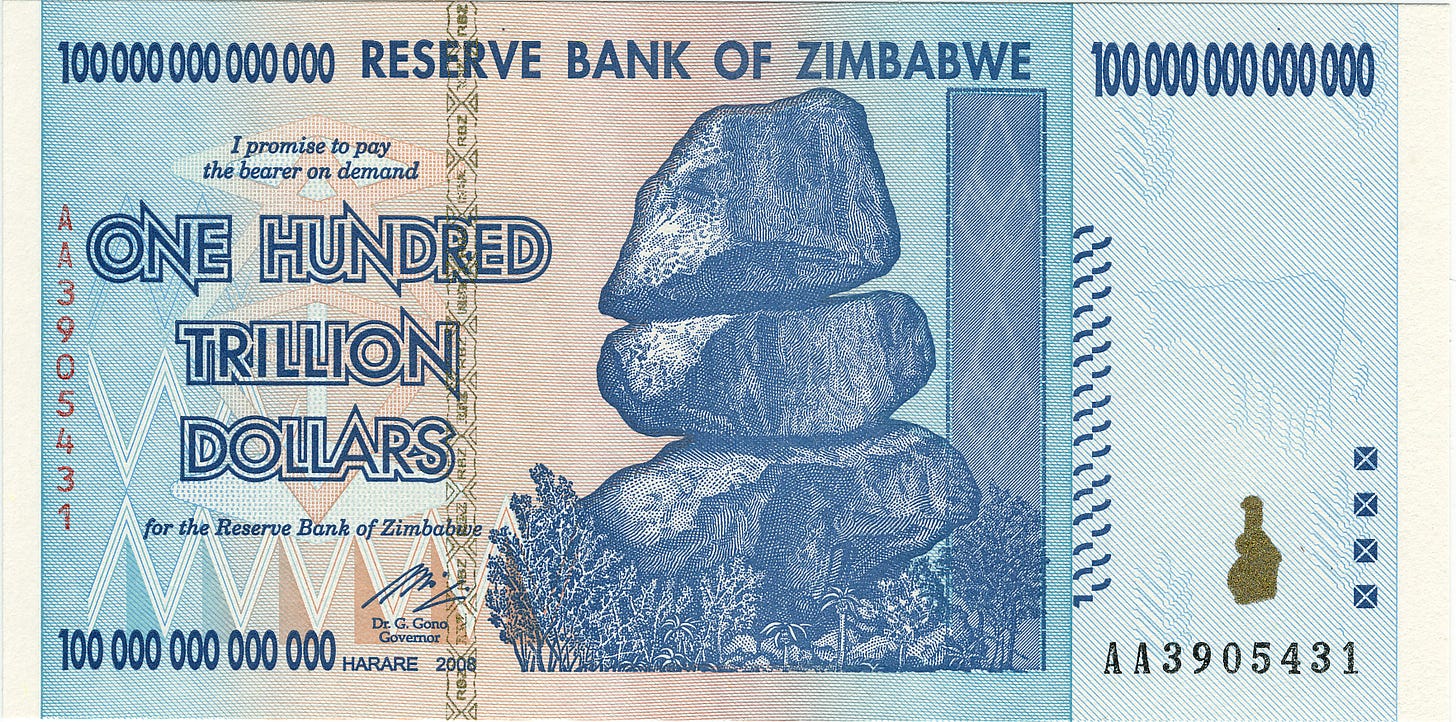

Seas shells, beads, gold, coins, paper notes, and electronic balance sheets have at various points been used as money. But none of these are money in themselves. People are rarely interested in pieces of paper or numbers on a bank website for their own sake. What matters is what money can buy you. Zimbabwe’s one hundred trillion dollar bill is a nice collectors item, but not valuable if all you can buy is a loaf of bread.

What people care about is what they can do with money—buy food, houses, heating, healthcare, clothes, and entertainment. In other words—how much they can consume the goods and services that others produce. This is the difference between the nominal value of money and its real value.

In a world before money, we might keep a stock of the carrots we grew or swords we smithed to swap for bread from the baker or beer from the brewer. But because it’s difficult to store carrots for too long or store the services that a physician provides for later bartering, we instead store a claim on future goods and services. We keep track of these claims by swapping IOU notes. That claim is money. Having more money means you have access to a larger share of available goods and services. The relative supply of carrots and market demand for those carrots determines its value and what it’s worth in IOU notes.

We collectively agree that paper with a head of state or historical figure, beads, gold, or Bitcoin have some value, typically because they’re fixed in amount or we can control how much there is. Ultimately, the total supply of these proxies for the space of the possible (read my book or perhaps listen to this podcast around 36:43) represent a share of the currently available goods and services—what we can make and what we can do.

Much like shares in a business, the amount of money you have is your share in a country’s productive capacities. This is most apparent when you retire.

Much like shares in a business, the amount of money you have is your share in a country’s productive capacities.

What is a pension, 401k, superannuation?

While you are working, you save up money for your retirement. Retirement is the time when you stop producing contributions to our collective goods and services and become exclusively a consumer of food, healthcare, housing, and gifts for your grandkids. We keep track of your post-production consumption ability using a pension, 401k, superannuation, or whatever other financial vehicles your society uses to accumulate retirement “savings”.

These savings are a promised stake of future production, but this promise, regardless of the size of your pension, is contingent on there actually being sufficient production; sufficient goods and services for you to consume. This in turn is a function of energy, technology, number of people, and their skills and education.

This is the problem that many countries face with falling birth rates and the relatively large population of Baby Boomers who are about to retire. Japan is a portend of things to come in many developed countries. Around 2011, Japanese newspapers reported that adult diapers had for the first time begun outselling baby diapers. There isn’t enough production to meet their consumption without undermining the ability of the working generation to consume for themselves or significantly decreasing their quality of life.

Without enough of the share of money for young people to buy a house and feel secure, the next generation struggle to settle down and start a family, reducing the birth rates and further reducing future production and future innovation. This transition to lower birth rates is sometimes called the demographic transition. Almost all countries go through it as they get wealthier.

So what do you do? Japan tried robots as a solution, but the technology didn't advance fast enough for this to be viable. Japan had no choice but to use a solution they had long avoided - immigration.

Japan is a highly homogeneous country with a general sentiment to keep it that way. But by 2019, the writing was on the wall. In April 2019, the new Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act came into effect. The conservative government led by then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe sold it as a necessary step for meeting the demands of business owners who needed selective, skilled migration. Immigrant numbers quickly hit record highs. Immigrants still represent just 2.5% of the population, but that percentage will continue to rise and new laws are in the works to continue the expansion, for example, streamlining the path for high skilled immigrants. Japan hasn’t figured out what model of multiculturalism it wants to use, a decision that will affect the future of Japanese society.

This is the solution most countries use - bring in new people. To solve this challenge of insufficient production, most countries expand their working population through immigration, but of course this requires other countries to have above replacement birth rates and has all of the challenges we discussed in Chapter 7. In an economically effective immigration system, countries compete for the most productive immigrants, who create more wealth than they consume through the social welfare state.

Without such a replacement in production, the price of everything goes up as each dollar represent less goods and services. What matters is how many loaves of bread or other essentials your $100,000, one million, or one trillion dollars buys you. What matters is that there’s enough to go around for both the working and retired to have a reasonable division of consumption. If there isn’t enough, either pensioners take a hit to their quality of life or young people can’t secure jobs that meet their needs, buy houses and start families. This leads to inequality between the young and old and discourages the desire to have children.

It’s a vicious feedback loop.

How do we measure how much there is to go around? Usually, through GDP.

What is GDP?

Gross domestic product or GDP is a measure of the production of goods and services in a country over some time period. It’s typically measured in money for want of a better metric, but it is ultimately an attempt to measure the space of the possible that our excess energy creates.

The United States has the highest GDP in the world, followed by China, Japan, Germany, India, United Kingdom, France, and Canada. But this is GDP overall. You can increase GDP by simply having more people. Each person adds more goods and services and so grows overall GDP. But often what we really care about is GDP per person.

GDP per capita is how much GDP there is per person (though of course this is unevenly distributed). This is sometimes adjusted for purchasing power—how much the same goods and services cost in each country—the difference between the nominal value and real value. The highest GDP per capita countries are typically those with highly productive, educated populations leading to innovation (such as the United States), or where there is access to large energy reserves (such as Saudi Arabia). Of the major high GDP world economies, the United States is still in the top 20 for GDP / person at $60k / person, but all other countries on the list above fall much lower. Small countries who are innovative, energy-rich, or both can have higher production per person than larger economies.

Some countries are wealthier than others. Some people, contribute more than the average. This is why high skilled immigration that meets missing needs in a country is so valuable.

This is why high skilled immigration that meets missing needs in a country is so valuable.

So “money” isn’t real. It’s a claim on a share of current production. Like shares in a company, money is shares in a country. How money is invested is an allocation over our current supply of energy, people, and resources. That allocation can be productive—a brilliant new start up—or unproductive—speculatively holding onto a property with no development for hope of increased value.

So how is money created?

How is money created?

Printing money rarely refers to the literal printing of bills. Instead, money is created through debt. When a bank makes a loan, it is creating money out of thin air.

The bank is often loaning money it doesn’t actually have the cash reserves to make. It’s all fine as long as not everyone tries to get their money out (this is referred to as a bank run) and enough loans are being paid back with interest.

That interest represents new money. When a business takes a loan, it uses that money to do something useful and create value, such as through goods and services. It then uses the profits to pay the bank back. When the money is used for wealth creation—the expansion of the space of the possible—rather than wealth appropriation—rent-seeking, then printing money has no effect on inflation. The interest rate where the creation of new money does not affect inflation is the neutral rate of interest. Money is created because the space of the possible expanded. Here, not creating new money would be deflationary - the value of the bills, notes, and coins would go up, incentivizing people to hold onto the money itself, which in turn would slow the economy. By corrolary, inflation encourages efficient allocation (investment) of money as we shall discuss in a moment.

Once upon a time, money was backed by reserves of gold. In theory, you could take your paper and coins and exchange it for some amount of gold. But even then, there was typically more money than gold reserves. Nonetheless the supply of gold restricted the supply of money, leading to booms and busts. The end of the Bretton Woods agreement in the early 1970s ended the need to keep gold reserves, avoiding booms and busts and allowing a central bank to control the money supply.

Before we continue, there are at least three important points worth emphasizing here. The first is that how you make money is essential—unproductive uses are simply claims with no growth in the space of the possible. Second, as discussed earlier, pensioners aren’t the only ones making an unproductive claim on our goods and services. So too are those who are using money accumulated over generations (this is a contentious point that I’ve removed from this post to not distract you, but you can read more about it in my book or maybe I’ll write a future post on it). And finally, we must be able to trust those who control the money supply both in how much money is created and in terms of how money enters the economy based on loans to ensure that inflation is kept under control. Those who can spend money before inflation effectively have more real money—the Cantillon effect.

Inflation is a powerful force that means that the current supply buys less and less goods and services over time. This is often a good thing.

What is inflation and what does it mean to invest?

The money supply must expand with the space of the possible. Because money is created through loans, interest rates are set to match the rate of expansion. If expansion is slow, rates should be low. If expansion is fast, the rate should be high. This neutral interest rate is difficult to figure out for multiple reasons, including that the rate that is set by a central bank has a delay in the effect on the economy. So central banks are constantly making their best guess and turning the knob higher and lower to try to get it right.

When done right, inflation is low enough and loans are made judiciously enough that people are incentivized to invest their money in ways that grow the space of the possible rather than simply driving up house prices or other forms of wealth appropriation.

In contrast, in a world of deflation, money itself becomes worth storing and so people are incentivized to not spend but hold onto their cash. This grinds the economy to a halt. Even money kept under a mattress will be worth more in the future. This in turn discourages investment and economic activity in favor of mattress hoarding. Much like what happens with gold.

In contrast, a little bit of inflation means that money stored under a mattress gradually becomes worthless, approaching the value of the paper it’s printed on. This means that people are incentivized to keep their money in circulation. In fact, they are incentivized to allocate their money in ways that grow faster than inflation. Some people do this directly by starting businesses or investing in the businesses of others such as through the stock market. Others hand it off to someone else to do that investment for them such as through mutual funds.

Putting your money into an interest-bearing bank account shifts the allocation decision to the bank. The bank then pays you an agreed return and takes the difference in how much money they actually made in loans (or their choice of investments). This incentivizes banks to lend money to people who are more likely to pay it back. Similarly, a bond hands your money over to those issuing the bond, allowing them to invest on your behalf and returning a share to you. Putting your money into a fund leaves the job to a fund manager. Putting it into a passive ETF like Vanguard allocates it into a large basket of companies, effectively putting it into the growth of the economy as a whole. Holding particular currencies is a bet on the particular country’s ability to produce future goods and services at a rate higher than others. Investment in specific companies is a bet that they will make more money than others. And so on. The goal is always to pick investments that are equal to or greater than inflation to maintain current wealth.

The trouble begins when true economic growth begins to slow—when the space of possible slows its expansion or even begins to shrink.

One of the most important, but least discussed ratios is government debt to GDP ratio—where the government is spending more than the country is producing. That is the government expenditure represents a large percentage of the country’s production. When this expenditure is not expanding the space of the possible—investment in research and development or means of acquiring more oil—but instead in costs that don’t grow the space of the possible, the country increases its risk of default.

When the economy slows, the interest rates is lowered, but at some point, interest rates are so low, but production is still low and then we are in trouble. The value of money erodes because less is being created. We can now see that ultimately, less is being created because energy return on investment (EROI) and cheap energy availability is falling, the energy ceiling is collapsing, and we’re running out of ways to innovate new efficiencies (again, you’ll have to read my book to understand this point).

There are a few important lessons here. Not all investments are equally good for growing the space of the possible. A bad use of money includes buying a property and sitting on it with no increase in value in the hope it will go up in the future. We’ll revisit this in a moment – it’s part of why land taxes and other taxes on unproductive money are critical. A bad system is one that incentivizes people to use money in unproductive ways.

I’ll stop here, but here’s some recommended reading:

My colleague Nick Barr, a world-leading expert on pensions has a fun and accessible paper on “Pension Design and the Failed Economics of Squirrels”

A rabbit hole of monetary and social change that happened after 1971:

The history of money is described well by Niall Ferguson in The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, Penguin, 2008; and by Jeffrey E. Garten in Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy, Amberley, 2021.

The history of key economic ideas see Lawrence H. White, The Clash of Economic Ideas: The Great Policy Debates and Experiments of the Last Hundred Years, Cambridge University Press, 2012; and for recent events, two books by Ben Bernanke, 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19 and The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath, both W. W. Norton, 2022 and 2015 respectively.

And of course, A Theory of Everyone puts the pieces together in a larger context of evolution, growth, and progress.

Best wishes,

Michael