Afghanistan is getting the government many want

99% of Afghans favor making sharia the official law of the land

Hi Lab,

Some unedited thoughts on the Afghan situation after listening to Biden’s speech on Monday:

In the wake of the Taliban takeover of Kabul, President Biden defended his decision to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan saying “We gave them every chance to determine their own future. What we could not provide them was the will to fight for that future.” But what future did the Afghan people want?

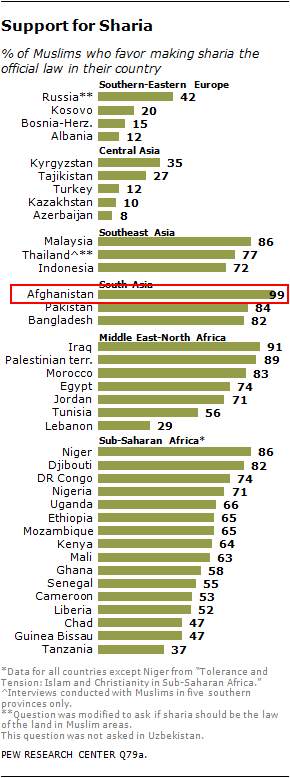

A 2013 Pew survey offers some insight:

99% of Afghans favor making Sharia the official law of the land – the highest percentage of all countries surveyed.

Sharia can mean different things to different people, so what do specific questions tell us?

81% of Afghans favor corporal punishment (like lashings) for theft

85% favor stoning as the punishment for adultery

79% favor a death penalty for leaving Islam.

These numbers point to a broader issue – our tendency to project our assumptions about the world onto others. Disastrously so when it comes to foreign policy. What works in one place won’t necessarily work in another.

Democratic institutions rest on invisible cultural pillars, such as rule of law and the desire for impartial rules applied impartially to all people. Where you are punished for breaking the law based on your actions not your connections. Where you have job opportunities based on your ability not the status of your tribe or brother-in-law.

Institutions are more easily transplanted than the norms on which they rest.

Afghanistan is high on strong kin-based cooperation; people rely on their kin for survival through support and favors. Even marrying among their extended family (the rate of cousin marriage in Afghanistan is 46%). Kin-based obligations undermine the kind of impartial institutions that liberal democracies are familiar with. Without these invisible cultural pillars, democracy collapses.

Human culture is the software of our minds, different adaptations to different circumstances and different histories. People in different places can run very different operating systems. Western assumptions about the universal desire for democracy and freedom are not borne out by the data.

But in the Taliban, the people of Afghanistan may get the government that many want. And from their perspective, perhaps a harsh, but fairer alternative to their previous regime, rife with partial politics and one of the highest rates of corruption in the world. The Taliban is here to stay. The question is where will this new Taliban and new Afghanistan choose to go?

Many nations, most notably those in Asia, have borrowed and recombined elements of successful institutions and adapted them to local cultures and circumstances. Western-style corporations and constitutions tailored to more collectivist cultures. If we want to help Afghanistan, we must meet them where they are, rather than where we want them to be.